A search for better anchor stowage

Anchors are a sailor’s conundrum. When menacing storm clouds approach our boat in harbor, we want the heaviest anchors possible. But when sailing, excess anchor weight on the bow becomes burdensome to our vessel, perhaps even dangerous.

When a summer storm approached us in the Falkland Islands, 300 miles east of Cape Horn, Brian and I took stock of the ground tackle aboard our Allied Seawind 30. We deployed three of our four anchors. As the wind backed Brian managed the anchor rodes until they were all tensioned and holding Dawn Treader in position against sustained winds over 60 knots. Our largest anchor lay straight ahead and two others flanked it, 30 degrees to port and starboard.We stood at the port-lights eating popcorn, watching dense clouds of spray fly by and listening to the wind hiss as it hit the water, like bacon in a hot pan.

Later that same month, as depression after depression passed through, we searched the forecast for favorable weather to sail west. With no weather window in sight, we eventually chose to sail upwind in a force seven. We hardened the sheets, heeled Dawn Treader to new limits, and tacked 150 miles against the near gale. As we punched through steep seas, the bow plunged heavily with each wave.

Although we had stowed much of our ground tackle low and amidships in preparation, the bow still carried an anchor and chain, or 200 pounds, for the coastwise trip. The laden bow amplified our boat’s motion in the waves and caused her to hobby-horse and lose drive. Nevertheless, we bashed on. It felt like the bow was hitting solid blocks instead of waves. We heard our forward toe rail crack and lost part of it to the sea.

The anchor conundrum grabs our attention in extreme conditions like these, but the problem also exists in-between extremes. Most cruising boats need heavy holding power, and most boats sail best without extra weight on the bow, especially upwind.

How much weight on the bow is too much? It is difficult to know where the line is, to know what exact weight creates problems. Instead of dwelling on a question that we cannot answer, we ask: how much weight can we remove from the bow? This question guides our search for better anchor stowage. Our search started well before our trip to the Falkland Islands and continues today.

In 2015 we built a below deck anchor locker while alongside a dock in southeast Georgia. We converted the center walkway notch in Dawn Treader’s v-berth into storage. We enclosed the notch with two pieces: a 30-inch high plywood panel on the aft side and an opening hatch on the top. This created a triangular compartment underneath the bunk. With the notch gone, the bunk was flush all the way across. Although the notch had been valuable, because it made entry into the forward bunks comfortable and easy, the space was amidships and low, and perfect for storing anchors.

The locker allowed us to carry our ideal anchor collection. It easily fit a 45-pound Mantus, a 44-pound Spade, a 33-pound Rocna, and an 11-pound Fortress. We passed these anchors in and out of the locker via the convenient overhead hatch. On deck, we used a Lofrans Manual windlass and two bow rollers to deploy and retrieve ground tackle.

Our anchor collection was complemented by four rodes. We carried 275 feet of chain in four lengths (150, 50, 50, and 25 feet), 3 of the four had 150 feet of nylon rode attached. We kept the longest chain in the chain locker. The two 50-foot long rodes were stowed in buckets atop the anchors in the anchor locker, and the last was typically kept attached to our Jordan Series Drogue.

In 2016 we sailed away from the east coast of the United States with our ground tackle secure in our new anchor locker. We crossed the Atlantic twice: first eastbound to the Azores, and then westbound across the equator to Brazil. From Brazil we sailed deeper south, into the Southern Ocean to the Falkland Islands. We were in those wind-swept islands in the Furious Fifties for over a year, and we put our anchor collection to work. When in doubt, put another anchor out, and we did, often.

The anchor locker we built served its purpose, however, it also caused problems. We knew we had compromised ergonomics by converting the notch. But it was startling that such a small shift made a fundamental impact on our life aboard. As time went on, we accessed the v-berth less and less. Ultimately, we stopped living in the forward third of our boat.

The aft bulkhead of the locker was an obstacle at the end of a squat, narrow passageway into the v-berth. To reach our bunk, we hunched over, squeezed through, and climbed up—all at the same time. Once we reached the v-berth platform we spun, 180 degrees into the horizontal position. It felt like break-dancing, not the start to a restful night’s sleep. If we forgot to turn on the anchor light, the scramble out and in again was even more annoying.

After the Falkland Islands, we sailed to Chile and Tierra del Fuego, where it was cold and damp. Airflow was hindered by the locker as much as we were. The air in the v-berth was stagnant and cold. We began sleeping in the main cabin near the wood stove, away from the condensation and mold that formed unchecked up forward.

For a couple of years we made the most of the otherwise uninhabitable v-berth by filling it with waterproof bags of assorted gear. We also added large produce hammocks between the fore and aft bulkheads. We had room for melons and pumpkins, and all sorts of stores. No matter how much we stored in the v-berth, however, it never made up the loss of our small boat’s living space. We were stuck in the main cabin.

In 2021 we set out to solve the problem, and others, on our growing jobs list. After months in the wilderness, sailing through the through the Straits of Magellan and north through Chilean Patagonia, we departed Chile. We sailed a 40 day nonstop passage to Mexico. We aimed for Mexico’s dry climate and a DIY friendly boatyard. Dawn Treader was situated on the hard there by the summer of 2022. Our primary goal was to prepare her for high latitude sailing. Step one: we needed to make the v-berth livable again. It was time to modify the anchor locker.

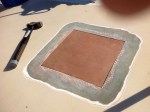

During our time in Chile, the incessant moisture had ruined the subpar plywood we had installed in 2015. We ripped out the delaminated and rotted v-berth platform and anchor locker and gathered the marine grade plywood, epoxy, fiberglass, and paint needed to rebuild.

We planned to build a reduced height anchor locker. Our compact, nestled stack of anchors (3 of our 4 anchors disassemble) measured 20 inches high. Without buckets of extra rode on top, we could stack and stow the anchors in a locker 10 inches shorter than the first one. Overall it seemed like a good solution, but we didn’t know if the reduction was enough. A 20 inch high bulkhead was still an impediment.

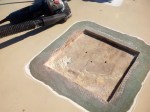

Just before we started reconstruction, Brian studied the space intently. He made a last-minute decision to cut out a section of the original plywood sole in the v-berth, in what had become the bottom of the anchor locker. He found more space for anchors under the sole, in the bilge.

The next day we built steadily. We built the new base of the anchor locker lower by going 6 inches into the bilge. The aft bulkhead of the locker was transformed, from an obstacle into a 14 inch high step.

Access to the v-berth improved dramatically. Now we step fluidly forward, onto the lid of the anchor locker. We also have space to swing our legs up and down, or in and out of bed—no more break-dancing.

With the anchor locker complete, the weight of chain in the bow remained a nagging question. Finally, after several months of refitting the boat, we realized there was space for chain underneath the sole in the head. When practical, we can now move our heavier, primary rode into new compartments, located low and center. When we do, we plan to sail with a lighter, secondary rode in the bow locker.

We built our first anchor locker in 2015 to solve a stowage problem. Unfortunately, the locker solved one problem and created another. We enjoyed the stowage solution and lived with its shortcomings for eight years. This time, we rebuilt to solve both problems. We preserved stowage and reclaimed access. We also got a little something extra in the refit process; we now have a new location for chain. We are counting the days until we put our solutions to the test, and the true testing ground is just a short trip in the travel lift, across the boatyard and into the sea.